Talk to anyone in fashion about the industry’s presence at COP28 and you’ll get a different response. Some applaud fashion for showing up in unprecedented ways, from announcing a major renewable energy agreement in Bangladesh to staging the annual UN conference’s first-ever fashion show. Others say fashion companies’ participation gives the illusion of bold climate action but, in reality, does very little at all.

COP negotiators are still working on the final agreement (it was meant to wrap yesterday, but COP summits rarely end on schedule). The preliminary draft released on Monday and the ensuing debate on Tuesday have left scientists, advocates, Indigenous communities and policymakers bracing for disappointment.

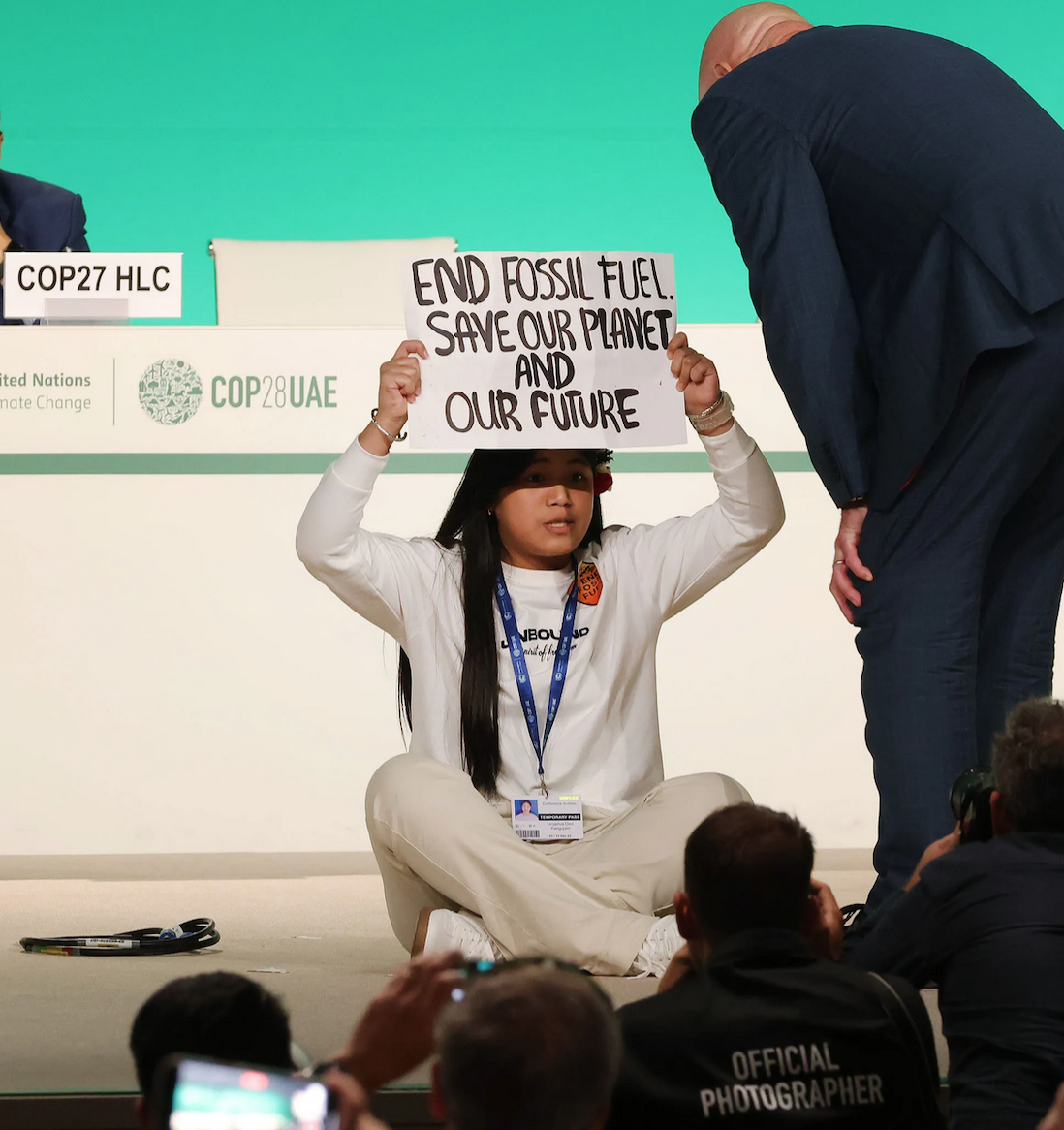

The clear consensus for what needed to happen at COP28 was a commitment to phase out fossil fuels — not simply reduce the world’s dependence on them, not to shift the burden to consumers or find ways to mitigate the impacts of coal, oil and gas, but to phase them out entirely — and emotions were peaking as delegates rushed to reach a new draft agreement in the waning hours. “We will not go silently to our watery graves,” John Silk, the head of the Marshall Islands delegation, reportedly said.

Phasing out fossil fuels — the single biggest contributor to global temperature increases — is the most fundamental and non-negotiable step needed to salvage a livable future on this planet. Fashion’s commitments seem to pale in comparison.

Still, the reality is that the world’s response to climate change is shaped directly by what individual countries and industries do about their own role in the crisis, and fashion has put itself forward as a leader on climate in recent years. The fact that another COP has come and gone with fashion a mere blip on the agenda is, for many, a disappointment. Brands and industry coalitions should have had greater prominence on the mainstage, critics say — and if the world is still overlooking fashion as a contributor to environmental problems, it’s the industry’s job to make its role better known. They also missed a clear opportunity to engage with other sectors, from food to transportation, where collaboration is not only possible, but necessary if they are to achieve their lofty goals.

“We all have this sustainability fatigue because we have all these big companies promising, promising, and thinking that we’re moving. We’re actually standing still — we’re standing still with the illusion of movement, but we’re not moving at all,” says Muchaneta Ten Napel, chair of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s Culture and Creative Industries Taskforce and associate lecturer at London College of Fashion.

Fashion wasn’t altogether missing from the climate summit. Bestseller and H&M Group pledged on 5 December to invest in a major offshore wind project in Bangladesh, and the Apparel Impact Institute announced on Monday that HSBC was committing $4.3 million over three years to the organisation’s Fashion Climate Fund, aimed at identifying and scaling tools to reduce carbon emissions in the supply chain. Both of those are major, transformative steps. Designers Stella McCartney and Gabriela Hearst spoke out on the need for legislation that incentivises rather than discourages more sustainable material sourcing, as well as the role of nuclear fusion in a clean energy future.

Such actions stood out for their level of commitment, or for pushing the boundaries of what fashion has addressed before. The industry made a handful of appearances elsewhere: LVMH announced an initiative to reduce the carbon footprint of its retail stores; Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana hosted a side event “to witness and deepen, in front of an international audience, the commitment of Italian fashion to sustainable practices” in collaboration with the UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion; and COP28 held a fashion show showcasing creations that are “wearable and accessible by everyone by collectively action-focused brands who are committed to achieve one goal: climate change and sustainability in the industry”.

But critics say that, as a whole, the industry hasn’t proved it’s committed to the necessary pace and scale of change. “They’re not showing up and taking action, they’re just showing up,” says Ten Napel. “It’s a very Trojan horse approach — we will be there, but we’re not there. [Companies are there to protect their] business interests, not to change the industry.”

What’s more telling than where fashion could be spotted during COP is where it was missing.

Where fashion should have been

Many operating both inside and out of fashion do not seem ready to acknowledge how intricately connected it is to so many other industries and ecological challenges — from agriculture and transportation to ocean health and Indigenous land rights. A key opportunity that an event like COP represents is to learn from and engage with all of those other sectors to understand how it can improve its own practices while liaising with other businesses, policymakers and activists to educate them and play a role in developing solutions.

“In the main plenary spaces, there will be a conversation about Indigenous land rights or the displacement of Indigenous communities and the oil industry, but fashion is not seen as relevant there,” says Samata Pattinson, CEO of cultural sustainability organisation Black Pearl and previously CEO at non-profit Red Carpet Green Dress. She organised several panels at COP28, including one on connections between biodiversity, climate and the role of culture in preserving both. “There’s a massive disconnect between the industry being represented at COP and the reality of the industry’s impact. Every single conversation, whether it’s Indigenous land rights, the phasing out of fossil fuels or plastics and ocean pollution — our industry has [potential to learn from] these solutions, and we need to be present to talk about our own contributions to these solutions and to these challenges. It’s all connected.”

Brands may not know where to start with that work: how does a large fashion conglomerate begin to understand how its cotton and wool supply chains, or its sourcing of metals like gold and copper, are implicated in an Indigenous community’s fight to keep control of its ancestral land? That’s not a task that most sourcing teams or even sustainability experts are experienced in — but that’s all the more reason to show up at meetings like COP.

Fashion also, she explains, not only has to improve its own operations, but has a role to play in shaping cultural values so that we think about and prioritise sustainability more inherently.

For as absent as major fashion companies have been at the climate summit, there’s a growing multitude of passionate individuals, like Pattinson, who are making waves. Ten Napel calls it a “cluster system” effect. “When it comes to those conversations where fashion needs to be in the room but isn’t, I’m learning that you need to identify where fashion needs to be and then you need to knock the door down and come in,” she says. “The bigger you are, the more you can make noise.”

Siloed thinking is a constraint not only on how companies and industries approach the challenges they face, but also on their success rates in addressing them, adds Nicolaj Reffstrup, co-founder of Ganni. “We drive a lot of carbon but we are never heard in regenerative agriculture discussions — we don’t play a part in that [conversation] or policymaking around it, or green chemicals or whatever other industry that pertains to what we do,” he told Vogue Business after speaking on a panel moderated by Ten Napel on Monday. “That’s a problem we are faced with daily. If we are to take full responsibility for the supply chain — which is virtually entirely outsourced and somewhat opaque — how can we do that if we are not part of the full ecosystem?”

Food policy experts are applauding the progress made at COP to recognise the role of the food and agriculture industries in climate — and to fund solutions to mitigate it, with over $3 billion in climate finance pledged for food and agriculture since the start of the summit, according to Bloomberg, although it still may be far from enough to yield the emission cuts necessary.

Daniela Chiriac, the manager for climate finance at Climate Policy Initiative, reportedly said in the Food & Ag Pavilion that the question is no longer if, but how, farmers should adopt more sustainable business models. Still for all the focus on agriculture, where was fashion?

Again, individual voices found their way. Ten Napel joined an agriculture-themed dinner the night before her panel, for example, where she learnt about farming practices that could be applied to fashion. Terence Eben, co-founder of Never Fade Factory in London, grows pineapples in Cameroon as part of a research project experimenting with pineapple and other bio-based textiles. While he attended some fashion panels at COP, he was also meeting with as many people from food and agriculture as he could, as well as monitoring conversations about energy because of the solar power he uses in Cameroon. Fashion s underrepresented, he says. “All the other sectors regarding SDGs [UN Sustainable Development Goals] and climate change are extremely strong.”

Moving forward

In a deal announced on 4 December, some of the world’s top multilateral development banks signed a joint declaration and launched a global task force to boost sustainability-linked sovereign financing for nature and climate. Led by the Inter-American Development Bank and US International Development Finance Corporation, the task force aims to reduce the funding gap between wealthy and poorer countries that blocks effective biodiversity conservation in the Global South by providing long-term fiscal solutions. That and other deals to invest in nature conservation, such as Norway donating $50 million to Brazil’s Amazon Fund and the Republic of Congo joining with the Wildlife Conservation Society to drive investment in high-integrity forests, are positive and urgent steps, says Nicole Rycroft, founder and executive director of the conservation non-profit Canopy — especially at this year’s COP, where fossil fuels took centre stage and the focus on nature, and nature-based solutions, that had been gaining momentum and was celebrated at COP26 has been “overshadowed”.

It’s important for global conservation: “There cannot be an expectation that those countries, those jurisdictions will forgo economic development opportunities and protect their natural resources, their forest ecosystems. There has to be mobilisation of capital to enable them to build conservation-based economies,” Rycroft says. But it’s also important for fashion to pay attention to the connection between climate, nature conservation and global finance.

Some forward-looking brands such as Kering, LVMH and Inditex are already investing in conservation, but much more is needed — both for fashion to reduce or mitigate its own ecosystem impacts, as well as to secure future supply chains for its own operations. “I think brands are already experiencing supply chain disruption due to climate change and biodiversity loss. There’s a recognition that part of having secure supply chains in the 21st century is the scaling of next-gen materials and, parallel with that, helping to stabilise planetary systems. Conservation of nature is integral to that,” she says.

The list of issues that fashion needs to be engaging in — and missed an opportunity to do so, by not showing up to COP to dialogue and learn as much as to speak make announcements on stage — goes on.

Ten Napel spells out a full list of areas where fashion could have had a stronger voice — or any voice at all — at COP28: Agriculture and Raw Materials, where “discussions should involve organic farming practices, reducing water usage and minimising chemical inputs” for materials such as natural fibres and natural dyes; Energy Use and Carbon Emissions, to focus on transitioning to renewable energy and reducing overall carbon emissions; Water Usage and Conservation, with fashion needing to address both water consumption and pollution; Chemical Management and Pollution Control; Climate Resilience and Adaptation; Sustainable Transportation and Logistics; and Social Responsibility and Labour Rights.

“Personally, I think that by participating in these conversations, the fashion industry can not only address its own impact but also contribute to broader environmental and social goals,” she says.

Read more – Vogue Business