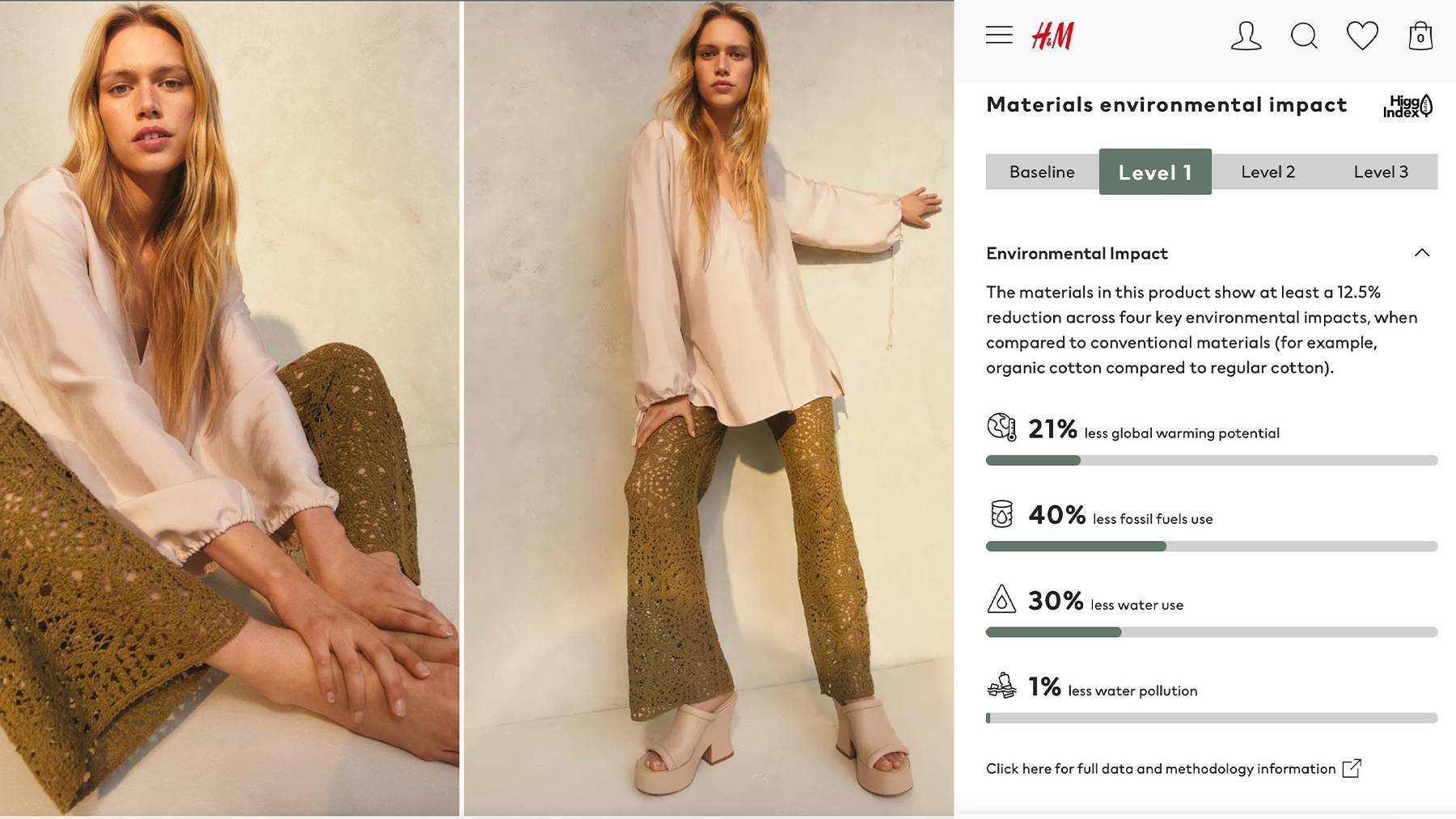

Last May, H&M introduced new scorecards designed to grade and market the sustainability credentials of materials used in select garments to shoppers.

A little like nutrition labels that detail the fat, sugar and protein content in foods, the fast fashion giant’s scorecards break down how fabrics perform in areas like global warming, fossil fuel use and water pollution. But there’s one major difference: nutritional labels on food products are strictly regulated by government bodies; sustainable fashion isn’t. That’s becoming more of a problem as sustainable fashion becomes big business.

Consumers, especially young ones, consistently rank sustainability as an important factor in purchasing decisions, even if price and cool factor remain bigger drivers. In response, brands have flooded the market with eco-claims and Earth Day capsules, but an absence of regulation has enabled a marketing free-for-all with plenty of space for greenwashing.

Sustainability labels like H&M’s are part of a trend in marketing towards greater transparency and accountability. In early 2020, Allbirds introduced a carbon calorie count for its products; last year Zalando stocked more than 140,000 products in its sustainable assortment; and brands including Moncler, Burberry and Chloé have committed to roll out digital IDs containing sustainability information.

But the labels currently used by retailers lack common standards and may cover a broad and varied set of criteria, from greenhouse gas emissions to living wages. Now, growing scrutiny from regulators is stoking an increasingly urgent debate over what “sustainable fashion” really means and how it should be measured.

The issue is coming to a head in Europe, where policymakers are set to lay out rules as soon as July governing how brands will be required to back up environmental claims.

Industry efforts to establish common standards have already embroiled brands, suppliers and trade groups in a battle for influence over how guidelines are framed. Meanwhile, industry watchdogs are campaigning to ensure issues like lack of independence, transparency and rigour that they say plague business-led standards don’t become further entrenched.

The stakes are high: bad labelling fails consumers, erodes trust in brands and puts efforts to reduce the industry’s impact at risk with misinformation that hampers attempts to drive real change. Rules governing the way claims are presented and the underlying metrics used to substantiate them also stand to create commercial winners and losers, with materials, products and brands that perform better gaining a positive green glow with consumers and those that underperform at risk of losing market share.

Ultimately, the debate comes down to a key question: what’s green and what’s greenwashing — and who gets to decide?

Read the full article on Vogue Business